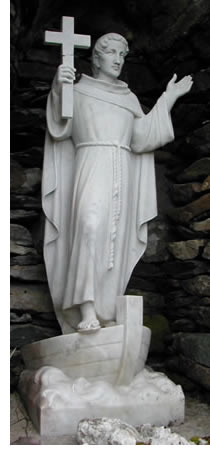

St. Brendan the Navigator

The story of St. Brendan's "Journey to the Promised Land" was

one of the most famous and enduring stories of western Europe

for almost a thousand years - a multi-language 'best seller'.

it may be that in his voyages in the Atlantic Ocean he reached

the shores of America long before Columbus. There is a renewed

interest internationally in this sixth-century Irish saint

whose name appeared on ocean maps through the centuries, and

whose story has been written in countless versions in many

languages.

The story of St. Brendan's "Journey to the Promised Land" was

one of the most famous and enduring stories of western Europe

for almost a thousand years - a multi-language 'best seller'.

it may be that in his voyages in the Atlantic Ocean he reached

the shores of America long before Columbus. There is a renewed

interest internationally in this sixth-century Irish saint

whose name appeared on ocean maps through the centuries, and

whose story has been written in countless versions in many

languages.

St Patrick is now the best known Saints of Ireland; but for perhaps seven centuries, up to the 16th century, that place was held by St. Brendan the Navigator. This was mainly because so many countries were fascinated for so long by the Navigato, the ninth century account of his travels in the Atlantic Ocean. Part of this fascination was caused by the way the story seemed to penetrate the vast mysteries of the Atlantic and part because the charm and literary skill with which events of the voyage and the personality of the Saint are depicted. In recent years the interest in the Saint has revived as it becomes more likely that the Navigatio may be the earliest account of Voyaging to America. This likelihood has been increased by the success of Tim Severin in 1977 in reaching Newfoundland by way of the Faeroes, Iceland and Greenland in a boat built according to the specifications laid down in the Navigatio, an adventure described in his book, The Brendan Voyage.

We know a fair amount about Brendan, thanks to the Navigatio and to several related, but occasionally conflicting, biographies. He was notable not only as a voyager, but also as a prominent leader of Irish Christianity in one of its great creative periods. He was born probably in A-D. 484 at a place now called Church Hill on a narrow ridge on the north shore of Tralee Bay, Co. Kerry, between Fenit Harbour, to the south, and Barrow Harbour. At the age of one he was, in accordance with custom, sent in fosterage to St. Ita, the mystic; this was the source of a famous and lifelong friendship between the two saints. After a life of activity, exceptional even by the standards of the sixth century, Brendan died, aged 93, in 577-8 at Annaghdown, Co. Galway.

Brendan belonged to what was called the Second Order of Irish Saints, also known as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. These included another Brendan (of Birr) hence the distinguishing title of' 'Navigator' given to our Brendan. These' Apostles' gave Irish Christianity its distinctive monastic character which it was to retain for some six centuries. In the monasteries, religion, learning and the arts were fostered and developed until, Ireland having been largely Christianized, there spilled over into Britain and continental Europe that great missionary, cultural and intellectual movement that up to the 11th century was to contribute so much to the slow recovery of European civilization after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Brendan's Irish foundations were Ardfert, near his birthplace; Inisdadroum (now Coney island) in the River Shannon close to Ennis, Co. Clare; another foundation on an island, Inchiquin in Lough Corrib in Co. Galway; Annaghdown by the Corrib in Co. Galway - a foundation for nuns of which his sister Briga became abbess; and his main foundation at Clonfert by the Shannon in Co. Galway. He also had foundations in Scotland (near St. Colm Cille's iona), Wales, Brittany and, most likely, the Faeroe islands. We read in the Navigatio that in all his foundations he had nearly 3,000 monks. His influence was widespread, not only in his native county and in other parts of Ireland, but also in Scotland, England and Wales and in continental Europe - Brittany, the Low Countries, Germany and along the Baltic coast to the Gulf of Finland.

He was an indefatigable traveler, as the spread of his foundations shows. There is a reliable account of his visiting Colm Cille in Scotland after 563. At that time Brendan was eighty. If we are to accept literally the account in the Navigatio, he was already in his mid-eighties when he set out on the great voyage that was to last seven years. As the young man he met in the Promised land at the end of the seven- year search said to him of that Land, 'You could not find it immediately because God wanted to show you his varied secrets in the great ocean .'

THE VOYAGE

There is no doubt about the impact of the tale, but was there really a voyage, and did it reach America? Let us look at the story in outline. It opens with an account of an abbot on an island monastery in Donegal Bay who often paid visits to the Promised Land of the saints by sailing some apparently short way out into the Atlantic. Brendan is fired with ambition to find this Land and, with fourteen picked monks, he goes to Brandon Creek, west of Mount Brandon in Kerry where, 'as is usual in those parts' (and still is !) they constructed a light, wooden-framed and ribbed boat. This they covered with skins. With three late-comers - who were to add drama to the voyage - they sailed west to find the Promised Land of the saints. They had no practical idea of where this island was but great confidence that God would, sooner or later, reveal it to them. Why did they not go north (instead of west) to consult with the abbot in Donegal Bay who clearly knew how to get to the Promised Land and back again? If they had, perhaps there would have been no tale!

Certainly, if that Promised Land was to be America we can, with hindsight, see that even in a keel-less boat - always at the mercy of changing winds - the conditions for success were there, as Tim Severin was to demonstrate in 1977. Some nine months later Brendan and his companions had clearly, by way of the island of St. Kilda, reached the Faroe Islands ('The Island of sheep') where each year they were to spend the period from Easter to Pentecost. There they met two important characters of the story, the mysterious steward who proved so helpful, and the amiable whale, Jasconius, who was content to pose as an island each Easter Sunday so that Mass could be offered on his back. The relationship began in an unfortunate manner when, at the first meeting, the voyagers - Sinbad-like - lit a fire on his back. He bore them no grudge and, on their last visit, showed some graceful emotion in taking them for a short farewell cruise! During the following autumn they reached an island which had the monastery of the Community of Ailbe, the Irish followers of a pre- Patrician Irish missionary, who had set out to seek their Promised Land many years before. Here, according to the Navigatio, Brendan's party were to spend each Christmas for five years. We get a charming if somewhat idealized picture of life in a monastery of contemplative Irish monks. It is not clear where this island was. There are references to a warm muddy pool and crystal which might suggest Iceland and Icelandic spar: but the general ambience is one of a very temperate climate, and the later context suggests a tropical latitude, perhaps the Azores, or indeed the Canaries, both also volcanic. We meet a 'soporific island' (possibly one of the Azores) and, some distance further on, what may be the Sargasso sea. in the following year we reach an island that is described as 'extraordinarily flat so much so that it seemed to them to be level with the sea. It had no trees or anything that would move with the wind, it was very spacious and covered with white and purple fruit'. This may have been one of the Bahamas, some of which do not rise more than 10 feet above the sea. (it was at one of the Bahamas - which he named San Salvador, now Watlings island - that Columbus, sailing from the Canaries in the wake of Brendan, but nine centuries later, was to make his first American landfall). some six days sail away was a very fertile island (Jamaica?) with 'grapes as big as apples' and 'a perfume like that of a house filled with pomegranate.' Then back to the Ailbe community for Christmas.

By now they had been two and a half years on the voyage. The narrative skips the adventures of the next four years, except to say that they spent Easter and Christmas in the usual places. The narrative resumes on what we can take from the description to be clearly the return voyage by way of the Bahamas-Bermuda (countless fish in crystal water), the Labrador- Greenland iceberg belt ('The Crystal Pillar') and two Icelandic volcanoes (the 'Island of Smiths' and the 'Fiery Mountain'), then by Rockall to Donegal Bay. There is a sharp break in the Southward thrust of the narrative after Rockall so as to retrace tracks to repeat the Easter visit to the Faeroes, and to pick up the 'steward' to act as pilot to the spiritual, as distinct from the material, Promised Land; but this is plainly a literary artifice. For one thing, the implication seems clear that the fog-enshrouded island (Newfoundland?) is here placed fairly close to Ireland, not where it belongs at the other side of the Atlantic. It is typical of the balanced composition of the tale that it should be made to begin and end with a visit to the Promised Land, however this may upset the orderly narration of the voyage. Close reading of the Navigatio shows it to be a masterly balance between precisely observed facts, vivid embroidery, and skilful story telling.

Weaving through the topographical details are accounts of the perils and hardships of the sea, vivid writing - as of the submarine volcano off Iceland, or the Dantesque account of the weekend leave of Judas from Hell spent on a wave- drenched, but cooling rock - and accounts of unfamiliar monsters.